| CONSTANCE MEYER Articles |

|

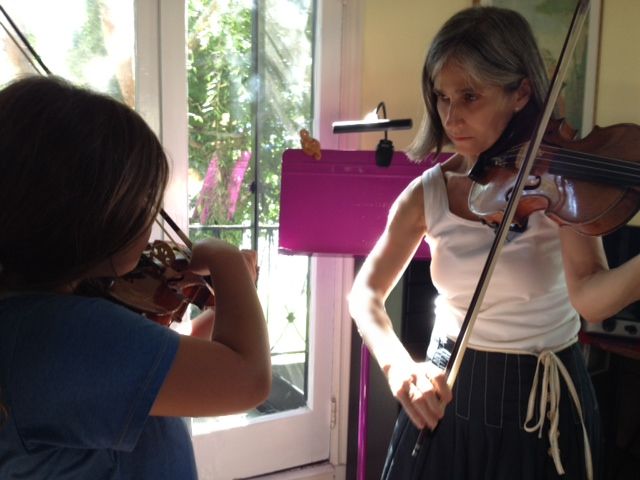

The Mom-centric method

The popular and successful Suzuki system of teaching a child a musical instrument -- begun by a Japanese violinist in the 1940s -- takes a family commitment. September 07, 2003 | Constance Meyer | The Los Angeles Times

Paik, now a homemaker in Torrance, has observed that "many American mothers think music is something special, that they can only do it when the kid is 'talented' or 'gifted.' They don't think the same way about sports." Not Paik. William, her 4-year-old, already studies piano. His sister, Erin, 6, is a violin student. They've both been studying for more than a year. Paik's far from being a stage mother, but she's not a soccer mom, either. She's a Suzuki mom. And that doesn't mean the kids are also riding choppers with training wheels.

While studying violin in Germany during World War II, Suzuki had an epiphany: A baby in a German-speaking family who hears the frequent repetition of such basic words as "Mama" and "Dada," he realized, easily begins speaking German, whereas babies growing up in Japan learn Japanese. Suzuki reasoned that very young children introduced to the violin in the same way could just as naturally learn to play it -- as long as they had the same loving and supportive environment. Suzuki called this method the mother-tongue approach. He also determined that for the child to be exposed to repetitions equivalent to what a baby experiences with language, she must have more than once-a-week-lessons. He proposed a triangle -- child, teacher and home teacher. Says Anna Guenthner of Wood Ranch in Simi Valley, mother of 7-year-old violin student Brieana: "It's not about dropping off your child and going to get your groceries." Mom's role usually the biggest

Asked whether she knew what she was getting into when she signed up seven years ago with her 5-year-old twins, banking consultant Teri Zakzook of Santa Monica says: "Not at all. I took piano lessons when I was young, and my teacher used to step on my foot as an exclamation point." Psychologist Laura Baker of Hancock Park -- mother of Morgan Cesa, 14 (piano), Colin Cesa, 12 (violin), and Cameron Cesa, 10 (cello) -- studied piano in her childhood and found her lessons "boring." Yet, she says, she got "hooked on the Suzuki method because I thought this is a really great way to start kids much younger, so they can get a lot further before they get to that point in their lives socially where they may decide they don't have enough time, and they can make those choices in a different way." For Baker, discovering boys when she was 14 distracted her from continuing music lessons. Not so with Morgan, who entered 10th grade this fall and has studied piano since she was 5. "She made the transition from being nagged to practice to being independent," Baker says. Moreover, her daughter doesn't do conventional baby-sitting. "She practices and does theory with six kids in the neighborhood." Stacy Belanger of Van Nuys, whose 10-year-old, Christopher, started violin when he was 6, describes her task as "to make the time available so we can practice, to really pay attention at the lesson. I take copious notes. We tape the lessons. The tape reminds us of things. I can say: 'Remember she said she wants you to do this and this and this.' "

Besides frequently hearing her mother play the pieces, the Suzuki student is required to listen daily to recordings of the music she will be playing. The idea is that she'll become so familiar with the Suzuki repertoire that she can sing it in her sleep and, once she has some technical facility, figure the pieces out on her instrument. Explains Beth Snowden-Ifft of Pasadena, an optometrist and mother of Susannah, 11 (violin), and Jim, 6 (violin): "They can then concentrate on technique and making music. They don't have to learn both the new instrument and the new skill of music reading at the same time." On the basis that one wouldn't dream of teaching reading to a baby still learning to talk, Suzuki separated those tasks. Belanger loves that "they go to bed singing, they wake up singing." Teachers routinely recommend books by and about Suzuki; "Nurtured by Love," a video of the film based on his book of the same name; and other material that can bring a parent up to speed on not only the pedagogy but the philosophy of the method. Many teachers urge prospective parents to attend an orientation course. The Colburn School of Performing Arts requires incoming Suzuki parents to take its class. Belanger appreciated the seven-week class given by the Suzuki Program of Los Angeles because it familiarized her with what her responsibilities were going to be. "It taught us to be more patient, make allowances, be more cognizant of how learning happens, to figure out how to make it fun." Does she ever lose her temper? Son Christopher is one of many kids who rolls his eyes at this question. After all, we're talking mothers and children here, not saints and angels. Audie Mark of Burbank, who grew up in Guatemala, was determined to give her child what was unavailable to her then. "Being a Suzuki mother is not easy. You have to be organized, flexible, on task," Mark says. "Every morning we wake up to the Suzuki music. It's my husband's job to push the button of the CD."

When Shinichi Suzuki died in Tokyo in 1998 at age 99, Mark says, "I cried.... I felt that I knew him. I felt that it was a wonderful thing that he did for society, not just for children. All a parent wants is the best for their children, and this is the best." For her part, Laura Baker says she "learned a lot about parenting through our music lessons. Teaching your children good habits and discipline is just something you need to do as a parent." Some Suzuki moms find an extra mile they're willing to go for their offspring. Brieana Guenthner, who began violin two weeks before her third birthday, describes a difficult time when her mother, an educator, was teaching in a classroom by day and finishing her master's degree at night: "My mom was working too much. We couldn't have so much time to practice." "So what did we do on the way to school?" Anna gently prods her daughter. "Practice in the car," whispers Brieana, as if she's not supposed to tell anyone. Anna laughs, remembering those days: "I was driving a little four-door ...." And Brieana played the violin wearing her seat belt? "Of course." Five-day music camps In addition to private lessons, group classes, master classes and recitals throughout the year, every summer there are more than 65 Suzuki Institutes (five-day music camps) across the United States alone. Most are held on college campuses. Each involves a few hundred campers -- accompanied mostly by mothers. The institutes are the high point of the Suzuki year. Late last spring, Anna Guenthner learned that a close friend of Brieana's from the previous two summers would be unable to attend this year's institute, so she asked her daughter if she still wanted to go. The reply: "Mom, that's the reason I've been practicing every week!" As it has for the past 15 years, the Southern California Suzuki Institute took place this summer at Occidental College in Eagle Rock. From July 20 through 25, the dorms were taken over by children of varying ages as well as many mothers. Some families chose to commute. For some, the event is their summer vacation. For Janis Simon of West Los Angeles, Suzuki camp began in June when she went with 10-year-old Mathew to the National Cello Institute, held in Claremont, and continued when she brought Elizabeth, 9, to the Occidental program for violinists. There, the thrill felt by children surrounded by other kids playing instruments was palpable. In addition to violin, the Occidental Institute includes classes for cello, viola, guitar and flute. A different parent education class was offered daily. Despite the considerable heat, students practiced under the trees scattered across the verdant campus. Audiences for the daily 11 a.m. and evening concerts literally hummed as parents and children, from infants to teenagers, all soaked up music. Benefit beyond the early years?

But according to Robert Lipsett, who holds the Jascha Heifetz chair at the Colburn School and is an associate professor of violin at USC, "if you look at all the great violinists, they probably had a parent who was a violinist or a musician who practiced with them, and the results were spectacular. Suzuki figured out a way for everybody to do that. He proved that anyone could play the violin." Lipsett adds: "Most of the 'players' coming up started with the Suzuki method. It's very good at making performing fun. If the teacher is sensitive, there's no reason why the student wouldn't develop well." Is there room for abuse? Certainly. No doubt there are some parents who miss Suzuki's main objective -- to build a beautiful character. But then again, there has always been room for abuse of children in the arts. The Suzuki method sets out a very simple plan. Anna Guenthner observes that some parents not involved with the method miss the point when they are simply stunned seeing a youngster play a very difficult piece. "They say, 'Wow, this little child can really play,' and I'm thinking, 'You have to go beyond that. It's more than that! It's a way of life.' " For Connie Paik, being a Suzuki mom is not such a big deal. "If my kid wasn't doing so well in soccer," she says, "I would practice kicking the ball with her in the backyard. We do the same thing, except kicking the ball is a lot easier than playing the violin." Returning from Germany to a Japan devastated by war, Suzuki wanted to give the children there something that would help them transcend hardships and unhappiness -- to live a more rewarding life. Today, some parents probably encourage their children to take up an instrument in hopes that it will boost their math skills or, years down the road, their chances of gaining admission to a good college. But beyond that, perhaps they sense what a deeply moved Pablo Casals, the great cellist and friend of Suzuki, said in 1961 after hearing 400 Suzuki students perform: "It may very well be music which will save the world." |

||

|

Note: |

|||

|

Constance originally coined the phrase "mom-centric," popularized in this article she wrote in 2003. - A. Tripp |

|||

|

Copyright 2003 Constance Meyer. All rights reserved |

|||

|

Site created, optimized and maintained by A. Tripp, TrippPR@gmail.com |

|||

Growing up in South Korea, Connie Paik

Growing up in South Korea, Connie Paik

The Paiks are part of a worldwide phenomenon -- parents and children enrolled in the Suzuki

method of learning a musical instrument. Developed in the 1940s by

Japanese violinist

The Paiks are part of a worldwide phenomenon -- parents and children enrolled in the Suzuki

method of learning a musical instrument. Developed in the 1940s by

Japanese violinist

For many parents, the Suzuki method, like Jell-O or Kleenex, is a respected brand name,

which gives it a kind of authority. The surprise is that while

sometimes the role of home teacher is played by a father or other

caregiver, it usually goes to the mother, whether she has ever

picked up a violin or not. In addition to playing recordings of the

Suzuki repertoire, she must be well versed enough in violin playing

to instruct her child.

For many parents, the Suzuki method, like Jell-O or Kleenex, is a respected brand name,

which gives it a kind of authority. The surprise is that while

sometimes the role of home teacher is played by a father or other

caregiver, it usually goes to the mother, whether she has ever

picked up a violin or not. In addition to playing recordings of the

Suzuki repertoire, she must be well versed enough in violin playing

to instruct her child. Given the ages of many Suzuki beginners, misunderstandings are inevitable. One mother found

her child in the bathtub using a soapy washcloth on her violin. That

afternoon, her teacher had instructed her to clean the instrument

"every day, just the way you get cleaned every day."

Given the ages of many Suzuki beginners, misunderstandings are inevitable. One mother found

her child in the bathtub using a soapy washcloth on her violin. That

afternoon, her teacher had instructed her to clean the instrument

"every day, just the way you get cleaned every day." Mark was attracted to

the Suzuki method because of what she read about its "training the

ear." But practicing with 9-year-old Anthony day after day since he

began at 4 has given her compassion for what he is trying to do: "It

taught me it's not easy to hold the violin -- and my motor skills

are as developed as they're going to be."

Mark was attracted to

the Suzuki method because of what she read about its "training the

ear." But practicing with 9-year-old Anthony day after day since he

began at 4 has given her compassion for what he is trying to do: "It

taught me it's not easy to hold the violin -- and my motor skills

are as developed as they're going to be." Some professional

musicians are disdainful of the Suzuki method. Soloist and teacher

Stuart Canin, a onetime concertmaster of the San Francisco Symphony

who's now concertmaster of Los Angeles Opera, says: "I've seen

extraordinarily good work in the very early years. But if it goes on

too long, it can be detrimental to the musical development of a

gifted student."

Some professional

musicians are disdainful of the Suzuki method. Soloist and teacher

Stuart Canin, a onetime concertmaster of the San Francisco Symphony

who's now concertmaster of Los Angeles Opera, says: "I've seen

extraordinarily good work in the very early years. But if it goes on

too long, it can be detrimental to the musical development of a

gifted student."