| CONSTANCE MEYER Articles |

|

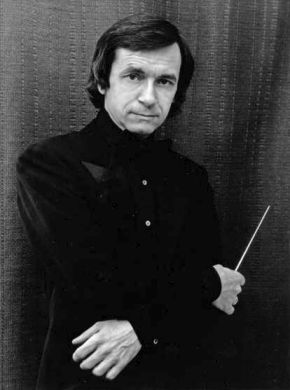

Soviet Conductor Surpasses Translation

Constance Meyer is a Los Angeles violinist who played in the orchestra during the Kirov Ballet engagement in Shrine Auditorium May 27, 1986 | by Constance Meyer | The Los Angeles Times

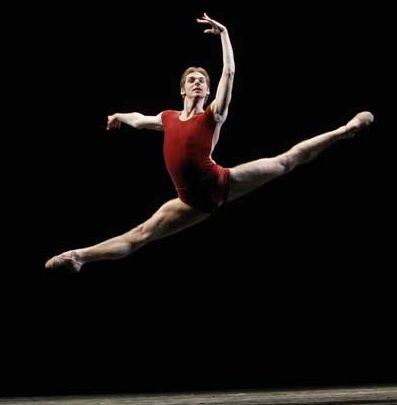

The local musicians selected to play during the Kirov Ballet's one-week engagement here had one day of rehearsal preceding the first " Swan Lake" last Wednesday. In the rehearsal room on the third floor of Shrine Auditorium the orchestra assembled early, eager to begin.

If any musician among us had yawned over the prospect of playing for yet another full-length production of "Swan Lake," that sentiment was corrected a moment later at the downbeat. Our "conductorrr" was Evgeny Kolobov, a 40-year-old man who joined the Kirov five years ago. Like an actor preparing for his role, Kolobov's face clouded over with seriousness as he began the opening sweeping bars of the score.As the intensity increased, our maestro's breathing became audible, an occasional hum perceptible. From the moment Kolobov submerged himself and us in Tchaikovsky's prelude, it was clear that he had superb stick technique. Nothing is ambivalent in it, or left to chance. He is easy to follow.

Later, the violins began a romantic passage. Kolobov stopped us, and to demonstrate what was missing he stroked his face with the palm of his hand in a loving caress. We played it again. With that gesture, the passage had been stripped of any aggressiveness and was now pure, gentle lyricism.The orchestra was momentarily jarred from the proceedings when a group of men, some in gray suits, others in navy, appeared in the doorway, to observe us.

"Ken." This is the first time we'd heard Kolobov speak. In spite of seeing his translator behind him, we were startled by this sudden reminder of the language barrier. Until this point extended verbal communication had been unnecessary. "Ken," he repeated tentatively and then burst into impassioned, fast Russian.

"You may take as much time as you want there. It is your moment," a Russian-speaking violinist translated. Ken Yerke nodded and began again. Kolobov's shoulders and thick square eyebrows raised with pleasure. "Prekrasna" (wonderful), he murmured. A little later we played a light dance which was not quite happy-go-lucky enough. He stopped us and pantomimed a carefree style. "Los Angeles!" he said, with an impish grin. The rehearsal lasted from 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. Normally we would have been exhausted. We were exhilarated. We broke for dinner and went home to change into our concert black. Everyone was instructed to wear a Kirov identity badge at all times. Failure to display it would mean non-admittance to the building. To get back to the pit, orchestra members had to walk through a mine field of about 20 men, some dressed in navy and some in gray. Clustered in small groups according to suit color, engrossed in intense conversation, eyeing everyone who passed by, they didn't appear to be typical balletomanes.

The unconfirmed rumor was that the ones in gray were Soviets, those in

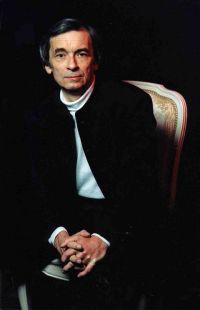

We returned to work. Kolobov had prepared us well. True to his style, no motion was unnecessary or unjustified. His eyes expressed the pathos, terror, gaiety, gravity--whatever mood was required as he coaxed out of the orchestra the effects needed.His gestures were unhampered by histrionics. Like a magnificent marionetteer, Kolobov's control of the various elements was never in doubt and yet his presence remained unobtrusive. Lest it be forgotten that the orchestra was secondary to what went on on stage, the dancers were met with wild applause.At the end of the entire performance Kolobov placed his hands on his heart and smiled at us. His sincerity was absolute.

|

This photo of Evgeny

Kolobov (right) is by Gary Friedman/LA Times.

|

|

Copyright 1986 Constance Meyer. All rights reserved

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Working with a great conductor is not a common event. But, like the thrill of seeing the

Working with a great conductor is not a common event. But, like the thrill of seeing the  At the rehearsal, an intense, boyish-looking, diminutive man snuffed out his cigarette and took his place on the podium.

"This is the conductor," a large blond woman announced, with a rolled Russian "r" at the end of conductor. She sat down directly behind him for future translation responsibilities.

At the rehearsal, an intense, boyish-looking, diminutive man snuffed out his cigarette and took his place on the podium.

"This is the conductor," a large blond woman announced, with a rolled Russian "r" at the end of conductor. She sat down directly behind him for future translation responsibilities.

Technique without musicianship is not inspiring. A rubato - a stretching here of the line to sustain a phrase, a momentary acceleration there for tension--all were so heartfelt and genuine that the orchestra instantly responded to him.

At the first break the musicians gathered into exuberant little groups of discussion. "That's how it should be!" a woodwind player said.

Technique without musicianship is not inspiring. A rubato - a stretching here of the line to sustain a phrase, a momentary acceleration there for tension--all were so heartfelt and genuine that the orchestra instantly responded to him.

At the first break the musicians gathered into exuberant little groups of discussion. "That's how it should be!" a woodwind player said. Our concertmaster began his cadenza.

Our concertmaster began his cadenza.

navy, State Department. Except for

navy, State Department. Except for