| CONSTANCE MEYER Articles |

|

Capturing a sound that rings true

Immortalizing a performance takes more than hanging a mike and hitting 'record.' There's an art to these engineers' science. December 2, 2007 | by Constance Meyer | Special to The Times

Yet just as in rock 'n' roll or hip-hop, the engineer for such music -- who is often, though not always, the producer as well -- is the person who makes or breaks an audio performance. He chooses and then places the microphones for a recording session and later meticulously splices various takes -- in the old days with a razor blade and tape, today on a computer -- to achieve the best possible version of a composition. It's a version that may well reach far more listeners than live performances of the work did even many years after its premiere.

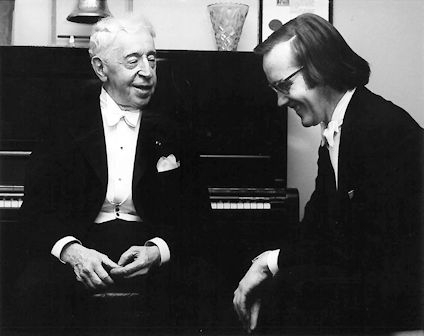

"Artur Rubinstein (above, left) never chose a take in his life with me," Wilcox recalls of his working relationship with the famed pianist. "But we were so closely allied in our musical feelings that I could tell pretty much from the recording session what he liked better, and since we wound up making about 60 LPs together, we were something like musical twins. He referred to me as his collaborator, not his producer."

Then, one day, Seetoo's father brought home a "used Telefunken reel-to-reel tape machine, so we could listen to the recordings again and again." The thing was, he explains, "If you own an illegal machine gun and there's something wrong with it, you can't have someone else fix it." And thus a technician was born. Over time, and out of necessity, Seetoo "would take things apart and try to reverse-engineer them," repairing belts, bushings, microphones, amplifiers and speakers.

Armin Steiner

Young Armin's keen ear was nurtured by the violin, which he began studying while a toddler. "Sound was of prime importance," he says, "how it projected." At the same time, he was acquiring technical know-how at home about recording and, inspired by his father's friend Michael Rettinger -- an acoustician and a leading engineer at RCA -- he went on to study acoustics at UCLA.

For Steiner, "music was a wonderful foundation and the engineering was

It's all in the setup

Lately, Vogler has been devoting a lot of his energy to recording Philharmonic concerts to be broadcast

on the radio and made available for downloading via iTunes. For both, he says, he uses the orchestra's "main microphone system, that captures most of the

sound, and 'spot' mikes, little area mikes that give a little more presence to the harp or the woodwind section -- or if there's a piano upstage that

sounds a little distant, we might enhance its sound. We record the three weekend performances, and then in conjunction with the assistant or associate

conductor we'll mix and match and put together the best performance." Lately, Vogler has been devoting a lot of his energy to recording Philharmonic concerts to be broadcast

on the radio and made available for downloading via iTunes. For both, he says, he uses the orchestra's "main microphone system, that captures most of the

sound, and 'spot' mikes, little area mikes that give a little more presence to the harp or the woodwind section -- or if there's a piano upstage that

sounds a little distant, we might enhance its sound. We record the three weekend performances, and then in conjunction with the assistant or associate

conductor we'll mix and match and put together the best performance."

For Steiner as well, "It's not necessarily the microphone that's in front of the section that is the important microphone picking up the sound. It may be the microphone that's 50 feet away. I hear many recordings that are a collection of microphones rather than the sound of an orchestra. The orchestra is not what you hear from left to right -- it's what you hear from front to back. It's the depth, the three-dimensionality, that gives the sound of an orchestra. Of course, those of us who have been in an orchestra have a better idea of what this should be. I approach my engineering from the player's viewpoint." Steiner laments that today, "Many engineers record all the sections of the orchestra independently, in isolation, in a booth, or in a section separated by dividers. But then you don't have the relationships sonically that you have when people are all playing at the same time. It's not a very musical approach." Perhaps not surprisingly, Seetoo considers chamber music the most difficult to record. Unlike the experience of attending a performance, where generally even a front-row seat is at least 20 feet from the musicians, preserving such a performance for posterity, he says, involves microphones "two to three feet away from them. It's immediate. It's a 'full spectrum' sort of music, polyphonic, because you have multiple voices going at the same time. You can't hide with chamber music. With orchestra, if someone in the back of the second violin section plays a wrong note, you can't hear the difference."

But according to Seetoo, "Postproduction is essentially a cut-and-paste job. If I didn't gather the material to begin with, I can't do anything at the end." Wilcox agrees. "While you can eliminate mechanical imperfections, you can't make someone an artist by making 400 splices," he says. "You can't give a violinist a more beautiful tone or a better conception of the music or a better idea of the tempo. You can make it sound mechanically and technically solid, but all the things that make 'music' can't be fabricated." That insight may help explain why Seetoo likens his job to being in the Secret Service. "I see and hear a lot," he says. "I know exactly how good or how bad one can play." For Wilcox too, the bond that the engineer-producer develops with artists is intensely personal: "You're dealing with the heart and soul of these people. You're their personal/musical physician/psychiatrist/cheerleader/best friend/advisor." Wilcox, for example, has been pianist Richard Goode's recording producer for more than 30 years. Of course, as iPods and MP3 players, with their thinner sound reproduction, proliferate, the work of these professionals may seem increasingly beside the point. But Seetoo, for one, thinks it's just a matter of time before download capability will enable listeners to hear

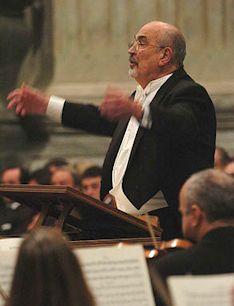

And besides, sheer serendipity can sometimes account for at least part of a recording's power. Vogler, for instance, recalls recording Paul Salamunovich conducting the Los Angeles Master Chorale in 1997 in "Lux Aeterna," by its then composer in residence, Morten Lauridsen."We were recording at Loyola Marymount Chapel, up on the hill, during one of the heaviest rains and wettest winters we've ever had in Southern California," Vogler says. "There was a full orchestra, full choir sessions all set up, and we had to somehow overcome the sound of the downpour outside and in the hallways." They wound up using mats to muffle that sound, and "it made the sessions kind of magical," he says. "If you listen to quiet passages in the piece, you can hear the rain. It added something to the recording, played a part in the lux aeterna, the 'eternal light.' "

|

|

|

Constance Meyer is a violinist and violin teacher in Los Angeles.

|

|

|

Copyright 2019 Constance Meyer. All rights reserved

|

|

Site created, optimized and maintained by A. Tripp, TrippPR@gmail.com

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rick RUBIN, George Martin, Timbaland,

Brian Eno, Phil Spector -- the average pop music fan, if asked, could probably come up with at

least a handful of names of notable recording personnel. It seems fair to say, though, that the typical consumer of orchestral and chamber

music recordings, faced with the same question, would draw a blank.

Rick RUBIN, George Martin, Timbaland,

Brian Eno, Phil Spector -- the average pop music fan, if asked, could probably come up with at

least a handful of names of notable recording personnel. It seems fair to say, though, that the typical consumer of orchestral and chamber

music recordings, faced with the same question, would draw a blank. Indeed,

Max Wilcox

(left), 78 -- who has won five Grammys and whose recordings have garnered 17 -- speaks for the majority of his

peers when he insists that his job is primarily musical: "I'm not a techie," he says. As a producer, Wilcox consults the musical score while supervising

a recording, and he brings to his task not only his background as a classical pianist but also experience as a conductor. "I have to be enough of an

audience to play for -- not that I'm so important," he says. The point, rather, is that the musicians being recorded are assured that "their musical

output is being monitored and evaluated, both by them during playbacks and by me."

Indeed,

Max Wilcox

(left), 78 -- who has won five Grammys and whose recordings have garnered 17 -- speaks for the majority of his

peers when he insists that his job is primarily musical: "I'm not a techie," he says. As a producer, Wilcox consults the musical score while supervising

a recording, and he brings to his task not only his background as a classical pianist but also experience as a conductor. "I have to be enough of an

audience to play for -- not that I'm so important," he says. The point, rather, is that the musicians being recorded are assured that "their musical

output is being monitored and evaluated, both by them during playbacks and by me." Recording engineer-producers often start out as electronic fiddlers, tinkerers. Take Chinese-born, New York-based

Da-Hong Seetoo, 47, who is engineer and producer for the Tokyo and Emerson string quartets as well as many other ensembles. Seetoo was 6, living in

Shanghai, when China's Cultural Revolution began and the record collection and huge sheet music library of his father, principal second violinist of

the Shanghai Symphony, were confiscated. Under cover of darkness, blinds drawn, windows closed, the elder man taught violin to Da-Hong

and his two siblings. The family also listened to "escaped" LPs that

circulated within the local musical community.

Recording engineer-producers often start out as electronic fiddlers, tinkerers. Take Chinese-born, New York-based

Da-Hong Seetoo, 47, who is engineer and producer for the Tokyo and Emerson string quartets as well as many other ensembles. Seetoo was 6, living in

Shanghai, when China's Cultural Revolution began and the record collection and huge sheet music library of his father, principal second violinist of

the Shanghai Symphony, were confiscated. Under cover of darkness, blinds drawn, windows closed, the elder man taught violin to Da-Hong

and his two siblings. The family also listened to "escaped" LPs that

circulated within the local musical community. In 1977, just after the Cultural Revolution, he came to the U.S. to study violin and then began pursuing a career as a

professional musician. Occasionally, he says, he would take an engineering job, "to help out friends." But suddenly, an "opportunity landed on me.

Eugene Drucker"

-- one of the two violinists in the

Emerson String Quartet

-- "was in the middle of completing the Bach solo

sonatas and partitas when the engineer fell ill, so he asked me if I

could help him. I was playing, but I needed to make a living. And

this stuff enables me to make a good living."

In 1977, just after the Cultural Revolution, he came to the U.S. to study violin and then began pursuing a career as a

professional musician. Occasionally, he says, he would take an engineering job, "to help out friends." But suddenly, an "opportunity landed on me.

Eugene Drucker"

-- one of the two violinists in the

Emerson String Quartet

-- "was in the middle of completing the Bach solo

sonatas and partitas when the engineer fell ill, so he asked me if I

could help him. I was playing, but I needed to make a living. And

this stuff enables me to make a good living." might say the same thing. Steiner, 73, works chiefly on film and television scores, but he is widely

regarded as being among the masters who engineer orchestral recordings. A native native Angeleno, Steiner was the son of a concert pianist mother and a

Hungarian international chess master father whose friends included many of the classical music emigres living in L.A. in the late '40s and early '50s.

As a hobby, he recalls, his father recorded "Hungarian Gypsy music in our house, direct to disk."

might say the same thing. Steiner, 73, works chiefly on film and television scores, but he is widely

regarded as being among the masters who engineer orchestral recordings. A native native Angeleno, Steiner was the son of a concert pianist mother and a

Hungarian international chess master father whose friends included many of the classical music emigres living in L.A. in the late '40s and early '50s.

As a hobby, he recalls, his father recorded "Hungarian Gypsy music in our house, direct to disk." Like Seetoo, Steiner became a professional violinist. But after several years of freelancing in New York and touring

as concertmaster of the

Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, he realized that "I didn't like this whole business of living out of a suitcase." That,

combined with the sudden death of his father, caused him to want to try something else. And so, with the help of an uncle, he built a recording studio

"in my father's chess club, over our garage on 108 N. Formosa."

Like Seetoo, Steiner became a professional violinist. But after several years of freelancing in New York and touring

as concertmaster of the

Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, he realized that "I didn't like this whole business of living out of a suitcase." That,

combined with the sudden death of his father, caused him to want to try something else. And so, with the help of an uncle, he built a recording studio

"in my father's chess club, over our garage on 108 N. Formosa." academic. I wanted to put these two things

together." Over the next 20 years, even after he was forced to give up his home studio, he worked with

Herb Alpert, Glen Campbell and numerous Motown

artists, among many others. Then, in 1980, he received an offer from 20th Century Fox to record some classical music with the Los Angeles Philharmonic

to be used on the soundtrack of television's "MASH." He still remembers the "menu" for that first date: "Tchaikovsky Sixth, Tchaikovsky

'Romeo and Juliet' and Stravinsky's 'Firebird.' John Williams and Lionel Newman conducted. It started a wonderful romance with that stage. I probably

did over 5,000 sessions between 1980 and 1992."

academic. I wanted to put these two things

together." Over the next 20 years, even after he was forced to give up his home studio, he worked with

Herb Alpert, Glen Campbell and numerous Motown

artists, among many others. Then, in 1980, he received an offer from 20th Century Fox to record some classical music with the Los Angeles Philharmonic

to be used on the soundtrack of television's "MASH." He still remembers the "menu" for that first date: "Tchaikovsky Sixth, Tchaikovsky

'Romeo and Juliet' and Stravinsky's 'Firebird.' John Williams and Lionel Newman conducted. It started a wonderful romance with that stage. I probably

did over 5,000 sessions between 1980 and 1992." Like

Wilcox,

Steiner

says he has "always considered myself a musician, even though I sit

on the other side of the glass. We don't create anything. We are

translators, translating what the composer put on paper, what we

hear as a result. I think that when you feel that you are bigger

than the music, you get yourself in big trouble."

Like

Wilcox,

Steiner

says he has "always considered myself a musician, even though I sit

on the other side of the glass. We don't create anything. We are

translators, translating what the composer put on paper, what we

hear as a result. I think that when you feel that you are bigger

than the music, you get yourself in big trouble." So what, exactly, are the challenges facing this special fraternity?

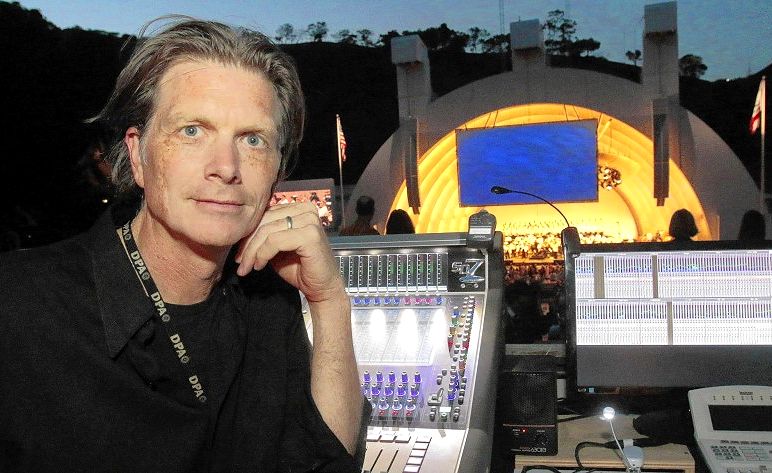

Fred Vogler, 43, is chief audio

engineer for the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Los Angeles Opera, the Los Angeles Master Chorale and summer events at the

Hollywood Bowl. He earned a degree

in recording arts at USC and interned at KUSC, and, he says, "Learning how to set up the equipment and everything that's associated with recording takes

a lot of experience to do right. It's no different from having a guitar and handing it to different people.

Some people are going to sound fantastic and

some pretty lousy."

So what, exactly, are the challenges facing this special fraternity?

Fred Vogler, 43, is chief audio

engineer for the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Los Angeles Opera, the Los Angeles Master Chorale and summer events at the

Hollywood Bowl. He earned a degree

in recording arts at USC and interned at KUSC, and, he says, "Learning how to set up the equipment and everything that's associated with recording takes

a lot of experience to do right. It's no different from having a guitar and handing it to different people.

Some people are going to sound fantastic and

some pretty lousy." The engineer, of course, can always combine takes. Steiner, for example, remembers being hired in 1956 to edit the Bach unaccompanied violin sonatas and partitas for Hungarian violinist

The engineer, of course, can always combine takes. Steiner, for example, remembers being hired in 1956 to edit the Bach unaccompanied violin sonatas and partitas for Hungarian violinist

"When

"When

"the real version" of recorded classical music.

"the real version" of recorded classical music.