| CONSTANCE MEYER Articles |

|

Tuba: The bass of the brass

Tuba players may be the Rodney Dangerfields of the orchestra, but the instrument has come a long way since its creation in the 1830s. January 18, 2004 | by Constance Meyer | The Los Angeles Times

That lack of respect has long plagued the tuba, a Johnny-come-lately to the modern orchestra. While the violin was perfected more than 300 years ago, the tuba didn't exist until the 1830s, when early versions began to evolve from the German ophicleide, a woodwind-like brass instrument that seems to have deeply underwhelmed composers.

After Berlioz, Wagner used so-called Wagner tubas in the "Ring" cycle, Stravinsky chose the tuba to accompany the Dancing Bear in the 1910 ballet "Petrushka," and Ravel highlighted it in his 1922 orchestration of Mussorgsky's "Pictures at an Exhibition." Where the double bass is the bass voice of the string family, the tuba, in all its varieties, became the bass voice of the brass. Still, there's George Kleinsinger's "Tubby the Tuba." Unlike Prokofiev's score for the narrated tale "Peter and the Wolf," it is not great music, but it resonates deeply with tuba players. Jim Self, one of the busiest in L.A., says: "I've lived it. Most tuba players have."

"Three years later," Johnson says, "I went to our band director and asked if I could join." The reply: " 'No, we have way too many trumpet players. But if you could play that thing back there' -- he pointed to something in the dark corner in the back

of the room, there's this dingy old-looking tuba -- 'If you could play that, you could probably be in the band. Soon.' "

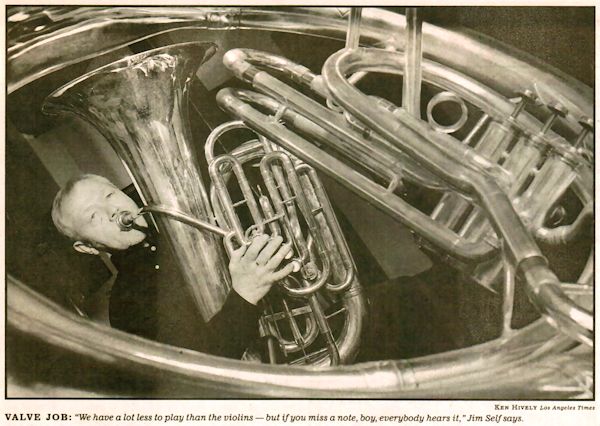

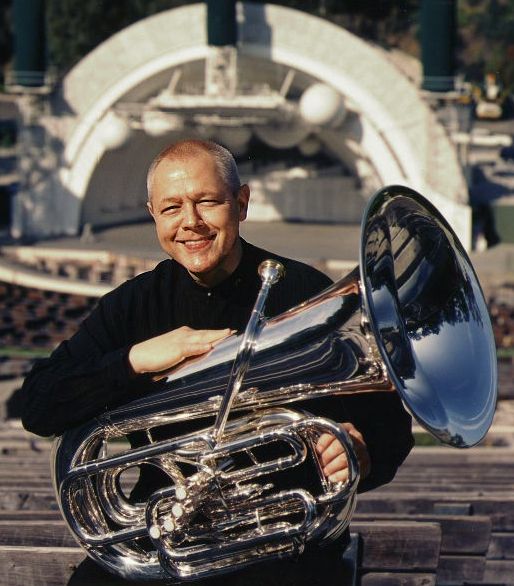

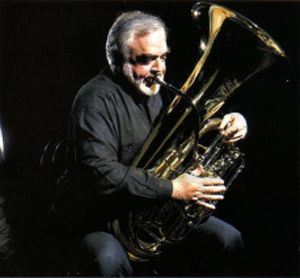

Tubist also a flubist

Today, when not playing in one of the five area orchestras he belongs to or on a recording date, Self is probably working in the stunning two-story studio behind his home in Laurel Canyon. "Jim eats, sleeps and breathes tuba," says the Philharmonic's Pearson, who has studied with Self, so it's not surprising to find a tuba-shaped window in the main room amid surfaces glistening with brass instruments and memorabilia. Self has recorded several CDs, both classical and jazz. The latest, "My America," even features an instrument he dreamed up: a tuba-sized fluegelhorn built for him by Robb Stewart of Arcadia. Self dubbed it the fluba. For Self, it's essential to commission and write music for the tuba that shows off not only his own abilities but the instrument's versatility. "It can't be a comic instrument," he says. "It can't be a buffoon. It can't be 'Tubby the Tuba,' getting out once a year in front of the orchestra."However, he acknowledges, "the low brass are considered the jokesters of the orchestra. We have a lot of free time and cut up, make jokes and drive everybody crazy. We have a lot less to play than the violins -- but if you miss a note, boy, everybody hears it." Apart from the potential peril of a resounding clinker, tubists face a couple of major hurdles. For one, they must be "doublers," capable of playing more than just their own instrument. They have traditionally doubled on bass trombone, cimbasso and sousaphone, but because they played double bass parts for early recordings -- on which the double bass proved inaudible -- they are often expected to be proficient bass players as well. More important, of the 90 or so musicians who make up a full symphony orchestra, there is only one tuba player. As Pearson puts it: "It can be 30 years before a job opens up." Arnold Jacobs, for instance, was 29 when he became the Chicago Symphony's tubist; he didn't retire until 45 years later. And the competition is so fierce that any opening attracts hundreds of applicants.

In the '50s, Phillips was a founding member of the New York Brass Quintet, which led many colleges that already had a string quartet in residence to add a brass quintet. He started and was the first president of TUBA -- the Tubists Universal

Brotherhood Assn., now called the International Tuba Euphonium Assn. He also commissioned hundreds of tuba pieces and encouraged other tubists, who did the same. The literature expanded

Movie spotlight

Unfortunately, Self will be absent from the huge tuba call for the Berlioz Requiem when the Philharmonic tackles that masterpiece in June (the composer's original orchestration called for six or seven tubas out of 500 musicians) because he'll be performing John Williams' Tuba Concerto with the Pacific Symphony.

Yet despite its improved status, the tuba has not entirely lost its talent to amuse. A few years ago, Johnson says, "I got this call: 'Can you play "Hava Nagila" on the tuba?' " The occasion, it turned out, was a surprise party for a woman engaged to be married, who frequently joked that she mustn't forget her ketubah, or Jewish wedding contract. Her friends, though, kept reminding her, "Don't forget to bring the tuba." "So I'm sitting in the middle of all these people and nobody asks, 'What are you doing here?' The door opens and I start to play and she says, 'The tuba!'

|

|

The following pictures appeared in the Los Angeles Times with this article by Constance Meyer:

|

|

|

|

Copyright 2004 Constance Meyer. All rights reserved

|

|

|

|

Children of the '50s and '60s may remember "Tubby the Tuba" -- the story, set to music, of a very shy brass instrument in a symphony orchestra. All Tubby wants is a solo. If his saga rings a bell, however, it's probably because of the narrator

of the 1947 recording,

Danny Kaye, and not the tuba player, Los Angeles musician George Bouje, who doesn't even get a credit on the CD version.

Children of the '50s and '60s may remember "Tubby the Tuba" -- the story, set to music, of a very shy brass instrument in a symphony orchestra. All Tubby wants is a solo. If his saga rings a bell, however, it's probably because of the narrator

of the 1947 recording,

Danny Kaye, and not the tuba player, Los Angeles musician George Bouje, who doesn't even get a credit on the CD version. Hector Berlioz wrote extensively about his dislike for the

ophicleide, and he was the first composer to write specifically for the modern tuba. Indeed, a three-week series of concerts the Los Angeles Philharmonic began Thursday to mark his bicentenary

means an unusually large amount of playing for the orchestra's tuba player, 46-year-old

Norman Pearson.

Hector Berlioz wrote extensively about his dislike for the

ophicleide, and he was the first composer to write specifically for the modern tuba. Indeed, a three-week series of concerts the Los Angeles Philharmonic began Thursday to mark his bicentenary

means an unusually large amount of playing for the orchestra's tuba player, 46-year-old

Norman Pearson. So why does anyone take up such an enormous, heavy and convoluted instrument, which can make a player look caught in the grip of a shiny boa constrictor?

Tommy Johnson, 69, another prominent local tubist, was the youngest of five children and the

only boy, and so, he recalls: "I definitely didn't want to play the piano or a stringed instrument." His father, a singer and choir director, suggested trumpet.

So why does anyone take up such an enormous, heavy and convoluted instrument, which can make a player look caught in the grip of a shiny boa constrictor?

Tommy Johnson, 69, another prominent local tubist, was the youngest of five children and the

only boy, and so, he recalls: "I definitely didn't want to play the piano or a stringed instrument." His father, a singer and choir director, suggested trumpet. (Jim)

Self

(Jim)

Self If there's a granddaddy to all these hopefuls, he's probably New York tubist

If there's a granddaddy to all these hopefuls, he's probably New York tubist

dramatically. Two important works that resulted in the mid-'50s

were Paul Hindemith's Tuba Sonata and Ralph Vaughan Williams' Tuba Concerto.

dramatically. Two important works that resulted in the mid-'50s

were Paul Hindemith's Tuba Sonata and Ralph Vaughan Williams' Tuba Concerto. There's no doubt the tuba has come a long way in 160 years. According to Johnson, "the instrument really took on a different role, not just a supporting role but also a solo role." In the movie "

There's no doubt the tuba has come a long way in 160 years. According to Johnson, "the instrument really took on a different role, not just a supporting role but also a solo role." In the movie " Certainly, L.A.-born

Certainly, L.A.-born